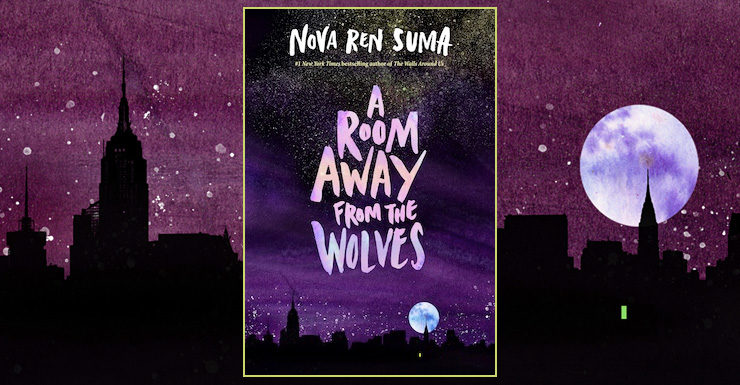

A Room Away from the Wolves is a ghost story set in a refuge for troubled girls deep in the heart of New York City. This boardinghouse is called Catherine House, named after the young woman who died a century ago, questionably and tragically, leaving her home open to future generations of girls. The house is filled with magical secrets and living memories, the downstairs rooms still decorated the way they were when Catherine was alive.

The original draft of A Room Away from the Wolves had an over-ambitious component that fell out of the story. There used to be some interspersed chapters written in a third-person, often omniscient voice that didn’t match the bulk of seventeen-year-old Bina’s narration. My intention was to use these pieces as a way to see the world from other eyes, but I came to realize that I didn’t need those eyes. In fact, the mysteries of the story felt more, well, mysterious when we were left guessing if the framed photograph on the wall above the fireplace really was watching Bina wherever she went, for example. Simply put, I couldn’t find a place for them anymore.

This chapter is the only one I regretted losing. It begins at night in the downstairs parlor of Catherine House, and reveals a never-before-seen perspective. For anyone who has read A Room Away from the Wolves and finds themselves curious about Catherine de Barra, her story is here…

“Night”

The girls are gathering again. They’ve come down to her front parlor, which was decorated in gold hues by her hand all those years ago and is still filled with her most precious things, and they violate her favorite room with their dirty shoes, their guffaws, their gum snaps, their chatter. She can’t plug her ears. She can’t move to another room. She has to sit in place, hands folded, stiff-backed, sucking in her cheeks and attempting a smile with her almost closed lips, listening, always listening. She does drift off, it’s difficult not to, but then a shriek will bring her back, or one of the girls will knock into an item of furniture and with a crash, she’ll snap to.

Nights have come and gone inside her house, decades’ worth of nights until she can’t tell the years apart. The last time she felt the golden carpet of this room beneath her feet, she was nineteen years old, hours before her accident.

Buy the Book

A Room Away From The Wolves

Night after night, the girls gather. She loses track of who is who. Sometimes she recognizes a distinct face shape, a hairstyle, and then next she looks the girl is gone and replaced by a different off-kilter version of what could be the same girl. She thinks. It’s so dim in the lamplight, she can’t be entirely sure.

This room contains so many items from her collection. When she was alive, she had shelves and tables brought in so she could display the most impressive pieces. She had the help dust every crevice and bare brass bottom, every porcelain lip, each and every day, the curtains open to allow in the light. The carved silver trays from Persia; the detailed figurines from Paris; the ivory tusks, smoothed and gleaming, from West Africa. These were gifts from suitors, from their travels. Men to whom she might be promised kept giving her item after item, thing after thing, until there was only one suitor left, the one her father most approved of and coveted as if for himself. James was the one he kept pushing toward her, ignoring the harsh way James spoke sometimes, the curl of his lip in the light when he tried to keep a pleasant smile. The gifts James brought often had sharp edges. The opal was as cold as winter frost and turned her finger blue the first day she wore it, but her father made her keep it on so James could see when he came calling. When he saw her with it, he said it reminded him of her eyes, and she felt as wicked and wrong as she ever had. She felt her wantings laid bare, her desire to escape all this and go running reflected in her eyes where she worried he could see.

These objects from her father, from suitors, were proof of the world outside this house, the world they were free to go see, while she stayed behind. It surrounded her—the low, humming brag of these souvenirs she didn’t buy for herself. This was her fate. She’d had dreams. Now they were squashed in these objects men had given her, and all she’d be able to do was coo, and say thank you, and give a chaste kiss.

One of the gifts was high on the wall, so if she strained to see it, she could just make it out. The mirror was a gift given to her by James—she had wished him dead at least a thousand ways and yet he hadn’t died. The mirror was cased in colorful glass, a rainbow prism around the plane that showed her face. If she looked out across the room, she could see herself seeing herself, reminding her of her captivity.

Tonight she doesn’t feel like listening to the girls who’ve taken over her house, but it’s difficult to keep what they say from seeping in through the translucent wall that separates her from the room. Vapid conversations about shoes, about lipstick shades. She used to be a part of conversations like this—when she was ill and had visitors at her bedside it was a good distraction—but now she can’t have any of it. Plum, raisin, hellcat, wine. Her lips are gray now. Her feet aren’t even in the picture.

She spies the girls lounging on her furniture. They finger her wall moldings. They dress for the night, some in bright colors, some with short skirt lengths and bare legs from hip to toe. They’ve silkened out their hair into straight sheets or they’ve tucked it up. Their shoes make them walk precariously and show off the dirty crevices between their toes.

They have plans to leave for the night, as they often do, but first, before pounding down her front stoop and leaving her gate unlocked and swinging out into the sidewalk, they like to pause here, in the front room, her best decorated, to wait for everyone to come down.

There are five girls, now, on the gold velvet couch. They kick off their shoes and the grimy soles of their feet rub up against her upholstery. There’s so much laughter and she can’t make out much of what they say. It takes effort for her to concentrate; sometimes they are here and gone, here and gone, and whole days and nights pass, and seasons change, and the grimy feet on her couch belong to other girls, and this is how time flows here if she doesn’t make an effort to hold in on one night, one group, one conversation.

It’s here that she realizes they have stopped. They’ve stopped to look at her.

“I swear that picture really is watching me wherever I go,” a blonde one says. “Look,” she says, leaping off the couch for a demonstration. She scoots to one side of the grand, carpeted room, up against the shelves where the teacups are posed, and she scatters them with her careless hand. “She doesn’t like that,” she says. “She’s looking at me now. See?”

She crosses again, to the other side, to where the long tasseled curtains cover the windows so no one passing by on the street could dare see inside, and says, “Look! The lady in the picture is still looking at me. God. What a creeper.”

Now all five girls are approaching. Wide eyes staring into her eyes. Getting closer to the gold frame that surrounds her, the dividing scrim of glass.

Inside the frame, she feels a charge of energy up her back, though she knows she can’t move, she can’t shift position in her chair, she can’t escape. At least, she hasn’t been able to, yet. She hasn’t found the strength.

She doesn’t like what the blonde had called her. A creeper.

“Catherine,” one of them singsongs at her, and how she loathes when they do that. “Hey in there. Stop snooping or we’ll put tape over your eyes.”

She’s not much older than they are—or she wasn’t, when her portrait was taken by the photographer with the big boxed camera on legs—it’s the style of clothes they don’t recognize, so they think her more pronounced in age. The dark color of her dress and the high collar were because she was in mourning. Her father died when she was eighteen.

The other girls are laughing now, at her, she realizes, at her eyes. They think her eyes are darting every which way, following where they go.

There are too many to look at all at once, so in fact she can let her eyes follow only one of them from this side of the room to the other, but they pretend she’s doing it to all of them. They swear her eyes are following them. They swear it to the grave.

Sometimes she wants one of the girls to come closer. Closer now, closer still. She wants one of the girls to reach a hand out, a single finger would do. Go on, she says through her closed teeth, her sealed gray lips. Touch.

The frame is a gilt-gold and enormous, and between her and the room is a sheet of glass. It’s not that thick. How close the girl would be to her, the girl’s finger to her face. If the girl touched near where the photograph showed her lips, she might feel it. She wonders if she could bite through, get teeth in the girl, give her a little nip. The sting of the bite, the mark it would leave . . . What would it feel like now, after all these years, to be alive?

Before her father bricked up the door so she couldn’t reach the roof, it was the only way her skin could truly feel the air. A window would not do. The fire escape—barred and ugly, cage-like around her body and steaming in the heat—wouldn’t do it either. Besides, her father didn’t allow her to climb outside where an innocent passerby or curious neighbor could see her. But the rooftop, flat and smoothed with a gummy layer of tar, was out of sight of the street—if she kept careful and away from the edge that overlooked the front of the house. Chimneys jutted up, but beyond that it was her and only other rooftops and sky.

She liked a touch of air on her bare arms, and even more tantalizing, her legs. She liked it best at night.

Her father thought she was asleep in bed then, and even though she was of age he always had a woman on hire to watch her. But the watching stopped when she entered her bedchamber and downed the lights. She was left alone to her tossing and turning. They didn’t know to listen carefully for the pattering of her bare feet up the back stairs.

The door seemed as if it would open into an attic. In any other house, it would do so, and there inside would be dusty furniture, chairs stacked on chairs, shrouded armoires. But this door had no room attached. It had only darkness on the other side, a stairway that turned darker still and then opened to the roof.

Before her father bricked it up, it led directly out.

When she was up there, she could be anyone. She was a steamship captain, surveying the wide swathe of uncrossable sea. She was an explorer, taking mountain passes on foot. She was a pilot in a soaring plane. All this she imagined on the rooftop as the wind rippled through her hair. The bad and the good. The impossible and the profane. She stood at the peak of the tallest tower built on the island of Manhattan (in truth her father’s house was five stories, but her mind cascaded that to twenty, thirty, forty, more). From there, she could see to the tip of the island and back. She could see the people who were awake, by their blazing windows, and she could see the people who were asleep, by their drawn shades. She could see the taxicabs and the vehicles on the roadways, and she could see the people walking too, when they passed, alone or together, under streetlamps. She could see like she never could when she was trapped inside.

But best of all was how it touched her.

The women touched her sometimes, the hired help, the nurses. Her mother had touched her—she remembered a feather-soft hand at her cheek—and the young men who came to visit always found a way to touch their lips to her hand, properly, in view of her father, though she suspected they’d do more if they were alone.

The touch of the air on the rooftop was different. It was forceful in a way she wasn’t used to, and warm in a raucous, dangerous way that tickled at her insides. It was electricity from toes to eyebrows. It was a fever and a clear, conscious mind. How it might feel to step out into it, to fly forward to where it led, which was everywhere and anywhere, on this night, on any night, on all nights that would have her. It belonged to her, and she to it. She’ll never forget it. It’s up there even now, even still.

If only she could climb those stairs again. If only one of the girls with their bare feet all over her furniture would stop being so selfish. All it would take is one girl to break the glass and help her escape this frame.

Just one.

Copyright © 2018 by Nova Ren Sum.

A Room Away from the Wolves is now available from Algonquin.

Nova Ren Suma is the author of A Room Away from the Wolves and the #1 New York Times bestselling The Walls Around Us, a finalist for an Edgar Award. She also wrote Imaginary Girls and 17 & Gone and is co-creator of FORESHADOW: A Serial YA Anthology. She has an MFA in fiction from Columbia University and teaches at Vermont College of Fine Arts. She grew up in the Hudson Valley, spent most of her adult life in New York City, and now lives in Philadelphia. Find her online as @novaren on Twitter and Instagram and at novaren.com.